“Jack” Lewis (1898-1963) wanted most of all to be known as a poet. Today we know C.S. Lewis as a great literary scholar, for works such as The Allegory of Love and English Literature in the Sixteenth Century Excluding Drama, including his scholarship on such poets as John Milton and Edmund Spenser — as a Christian apologist for dozens of titles including Mere Christianity and Miracles — for his fiction, including the seven books in The Chronicles of Narnia, and his critical success, Till We Have Faces. He was also famous for his Oxford lectures, and for his skilful debates against prominent atheists — but he is not well known for his poetry.

“Jack” Lewis (1898-1963) wanted most of all to be known as a poet. Today we know C.S. Lewis as a great literary scholar, for works such as The Allegory of Love and English Literature in the Sixteenth Century Excluding Drama, including his scholarship on such poets as John Milton and Edmund Spenser — as a Christian apologist for dozens of titles including Mere Christianity and Miracles — for his fiction, including the seven books in The Chronicles of Narnia, and his critical success, Till We Have Faces. He was also famous for his Oxford lectures, and for his skilful debates against prominent atheists — but he is not well known for his poetry.Too often Lewis is trying to win an argument — something that just doesn’t work in a poem. He had developed such a love for the form and subject matter of medieval narrative verse, that he could not relate to the poetic techniques of the twentieth century. In one poem he mocks the famous opening of Eliot’s “Prufrock” with the lines:

-------------For twenty years I’ve stared my level best

-------------To see if evening—any evening—would suggest

-------------A patient etherized upon a table;

-------------In vain. I simply wasn’t able...

Despite this short-coming Lewis understood medieval poetry better than perhaps anyone. He wrote many beautifully poetic passages in his other writings, and did successfully (though little acknowledged) write some fine poems.

The following poem captures his desperation, like a trapped animal — as he describes himself in Surprised By Joy as “the most dejected and reluctant convert in all of England” — when he realized the truth of Christ. I find the honesty he permits himself here — perhaps because it was written for a character in his book The Pilgrims’ Regress — most refreshing.

Caught

You rest upon me all my days

The inevitable Eye;

Dreadful and undeflected as the blaze

Of some Arabian sky;

Where, dead still, in their smothering tent

Pale travellers crouch, and, bright

About them, noon's long-drawn Astonishment

Hammers the rocks with light.

Oh, but for one cool breath in seven,

One air from northern climes,

The changing and the castle-clouded heaven

Of my old Pagan times!

But you have seized all in your rage

Of Oneness. Round about,

Beating my wings, all ways, within your cage,

I flutter, but not out.

To read my blog about why C.S. Lewis had such a timeless quality in so much of his writing (other than his poetry) visit: Canadian Authors Who Are Christian

This is the first Kingdom Poets post about C.S. Lewis: second post, third post

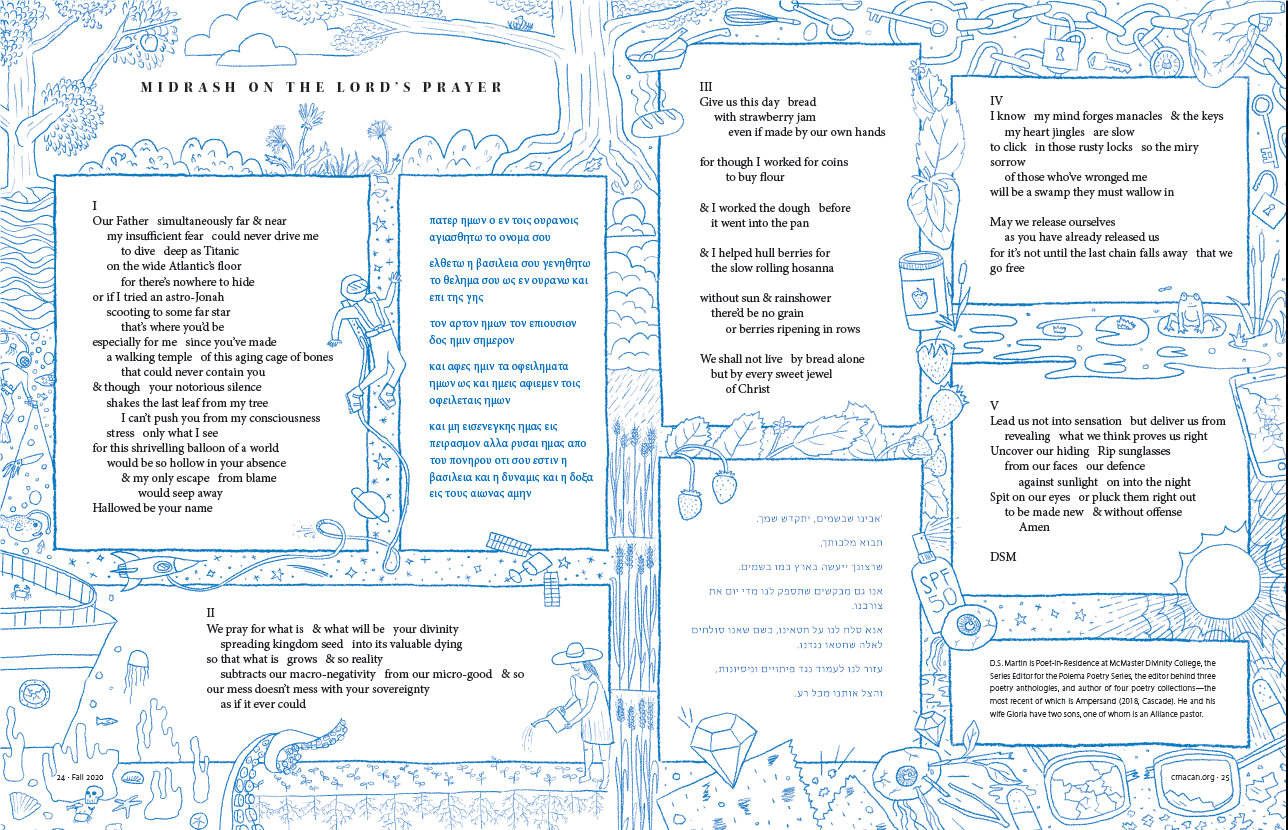

Entry written by D.S. Martin. He is the award-winning author of the poetry collections Poiema (Wipf & Stock) and So The Moon Would Not Be Swallowed (Rubicon Press). They are both available at: www.dsmartin.ca